Hip

- For other uses of the term, see hip (disambiguation).

| Hip (anatomy) | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Bones of the hip | |

| Latin | coxa |

| Gray's | subject #92 333 |

| MeSH | Hip |

In vertebrate anatomy, hip (or "coxa"[1] in medical terminology) refer to either an anatomical region or a joint.

The hip region is located lateral to the gluteal region (i.e. the buttock), inferior to the iliac crest, and overlying the greater trochanter of the thigh bone.[2] In adults, three of the bones of the pelvis have fused into the hip bone which forms part of the hip region.

The hip joint, scientifically referred to as the acetabulofemoral joint (art. coxae), is the joint between the femur and acetabulum of the pelvis and its primary function is to support the weight of the body in both static (e.g. standing) and dynamic (e.g. walking or running) postures.

Contents |

Anatomy

Region

The bones of the hip region are the hip bone (or innominate bone) and the femur (or thigh bone).

- Prominent palpable bony structures of the hip bone include the iliac crest, the anterior superior (ASIS) and posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS), the posterior inferior iliac spine (PIIS), the five or so tubercles and the lower lateral borders of the sacrum, and the ischial tuberosity ("sitting bone").[3]

- Proximally the femur is largely covered by muscles and, as a consequence, the greater trochanter is often the only palpable bony structure.Distally on the femur some more palpable bony structures are the condyles.[4]

Articulation

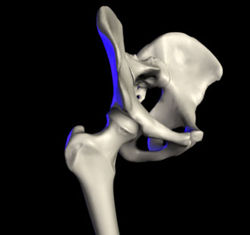

The hip joint is a synovial joint formed by the articulation of the rounded head of the femur and the cup-like acetabulum of the pelvis. It forms the primary connection between the bones of the lower limb and the axial skeleton of the trunk and pelvis. Both joint surfaces are covered with a strong but lubricated layer called articular hyaline cartilage. The cuplike acetabulum forms at the union of three pelvic bones — the ilium, pubis, and ischium.[5] The Y-shaped growth plate that separates them, the triradiate cartilage, is fused definitively at ages 14–16.[6] It is a special type of spheroidal or ball and socket joint where the roughly spherical femoral head is largely contained within the acetabulum and has an average radius of curvature of 2.5 cm.[7] The acetabulum grasps almost half the femoral ball, a grip augmented by a ring-shaped fibrocartilaginous lip, the acetabular labrum, which extends the joint beyond the equator.[5] The head of the femur is attached to the shaft by a thin neck region that is often prone to fracture in the elderly, which is mainly due to the degenerative effects of osteoporosis.

|

|

|

|

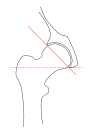

Transverse and sagittal angles of acetabular inlet plane.

|

||

The acetabulum is oriented inferiorly, laterally and anteriorly, while the femoral neck is directed superiorly, medially, and anteriorly.

The transverse angle of the acetabular inlet can be determined by measuring the angle between a line passing from the superior to the inferior acetabular rim and the horizontal plane; an angle which normally measures 51° at birth and 40° in adults, and which affects the acetabular lateral coverage of the femoral head and several other parameters. The sagittal angle of the acetabular inlet measures 7° at birth and increases to 17° in adults.[8]

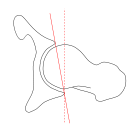

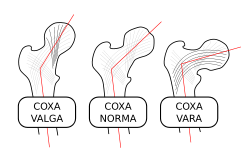

Femoral neck angle

The angle between the longitudinal axes of the femoral neck and shaft, called the caput-collum-diaphyseal angle or CCD angle, normally measures approximately 150° in newborn and 126° in adults (coxa norma).[9] An abnormally small angle is known as coxa vara and an abnormally large angle as coxa valga. Because changes in shape of the femur naturally affects the knee, coxa valga is often combined with genu varum (bow-leggedness), while coxa vara leads to genu valgum (knock-knees). [10]

Changes in CCD angle is the result of changes in the stress patterns applied to the hip joint. Such changes, caused for example by a dislocation, changes the trabecular patterns inside the bones. Two continuous trabecular systems emerging on auricular surface of the sacroiliac joint meander and criss-cross each other down through the hip bone, the femoral head, neck, and shaft.

- In the hip bone, one system arises on the upper part of auricular surface to converge onto the posterior surface of the greater sciatic notch, from where its trabeculae are reflected to the inferior part of the acetabulum. The other system emerges on the lower part of the auricular surface, converges at the level of the superior gluteal line, and is reflected laterally onto the upper part of the acetabulum.

- In the femur, the first system lines up with a system arising from the lateral part of the femoral shaft to stretch to the inferior portion of the femoral neck and head. The other system lines up with a system in the femur stretching from the medial part of the femoral shaft to the superior part of the femoral head.[11]

On the lateral side of the hip joint the fascia lata is strengthened to form the iliotibial tract which functions as a tension band and reduces the bending loads on the proximal part of the femur.[9]

Capsule

The capsule attaches to the hip bone outside the acetabular lip which thus projects into the capsular space. On the femoral side, the distance between the head's cartilaginous rim and the capsular attachment at the base of the neck is constant, which leaves a wider extracapsular part of the neck at the back than at the front[12]. [13] The strong but loose fibrous capsule of the hip joint permits the hip joint to have the second largest range of movement (second only to the shoulder) and yet support the weight of the body, arms and head.

The capsule has two sets of fibers: longitudinal and circular.

- The circular fibers form a collar around the femoral neck called the zona orbicularis.

- The longitudinal retinacular fibers travel along the neck and carry blood vessels.

Ligaments

|

|

|

|

Extracapsular ligaments. Anterior (left) and posterior (right) aspects of right hip.

|

||

|

|

|

|

Intracapsular ligament. Left hip joint from within pelvis with acetabular floor removed (left); right hip joint with capsule removed, anterior aspect (right).

|

||

The hip joint is reinforced by five ligaments, of which four are extracapsular and one intracapsular.

The extracapsular ligaments are the iliofemoral, ischiofemoral, and pubofemoral ligaments attached to the bones of the pelvis (the ilium, ischium, and pubis respectively). All three strengthen the capsule and prevent an excessive range of movement in the joint. Of these, the Y-shaped and twisted iliofemoral ligament is the strongest ligament in the human body. [13] In the upright position, it prevents the trunk from falling backward without the need for muscular activity. In the sitting position, it becomes relaxed, thus permitting the pelvis to tilt backward into its sitting position. The ischiofemoral ligament prevents medial rotation while the pubofemoral ligament restricts abduction in the hip joint. [14] The zona orbicularis, which lies like a collar around the most narrow part of the femoral neck, is covered by the other ligaments which partly radiates into it. The zona orbicularis acts like a buttonhole on the femoral head and assists in maintaining the contact in the joint. [13]

The intracapsular ligament, the ligamentum teres, is attached to a depression in the acetabulum (the acetabular notch) and a depression on the femoral head (the fovea of the head). It is only stretched when the hip is dislocated, and may then prevent further displacement. [13] It is not that important as a ligament but can often be vitally important as a conduit of a small artery to the head of the femur. This arterial branch is not present in everyone but can become the only blood supply to the bone in the head of the femur when the neck of the femur is fractured or disrupted by injury in childhood.[15]

Blood Supply

The hip joint is supplied with blood from the medial circumflex femoral and lateral circumflex femoral arteries, which are both usually branches of the deep artery of the thigh (profunda femoris), but there are numerous variations and one or both may also arise directly from the femoral artery. There is also a small contribution from a small artery in the ligament of the head of the femur which is a branch of the posterior division of the obturator artery, which becomes important to avoid avascular necrosis of the head of the femur when the blood supply from the medial and lateral circumflex arteries are disrupted (e.g. through fracture of the neck of the femur along their course).[15]

The hip has two anatomically important anastomoses, the cruciate and the trochanteric anastomoses, the latter of which provides most of the blood to the head of the femur. These anastomoses exist between the femoral artery or profunda femoris and the gluteal vessels.[16]

Muscles and movements

The hip muscles act on three mutually perpendicular main axes, all of which pass through the center of the femoral head, resulting in three degrees of freedom and three pair of principal directions: Flexion and extension around a transverse axis (left-right); lateral rotation and medial rotation around a longitudinal axis (along the thigh); and abduction and adduction around a sagittal axis (forward-backward) [17]; and a combination of these movements (i.e. circumduction, a compound movement in which the leg describes the surface of an irregular cone)[14]. It should be noted that some of the hip muscles also act on either the vertebral joints or the knee joint, that with their extensive areas of origin and/or insertion, different part of individual muscles participate in very different movements, and that the range of movement varies with the position of the hip joint. [18] Additionally, the inferior and superior gemelli may be termed triceps coxae together with the obturator internus, and their function simply is to assist the latter muscle.[19]

The movements of the hip joint is thus performed by a series of muscles which are here presented in order of importance[18] with the range of motion from the neutral zero-degree position[17] indicated:

- Lateral or external rotation (30° with the hip extended, 50° with the hip flexed): gluteus maximus; quadratus femoris; obturator internus; dorsal fibers of gluteus medius and minimus; iliopsoas (including psoas major from the vertebral column); obturator externus; adductor magnus, longus, brevis, and minimus; piriformis; and sartorius.

- Medial or internal rotation (40°): anterior fibers of gluteus medius and minimus; tensor fascia latae; the part of adductor magnus inserted into the adductor tubercle; and, with the leg abducted also the pectineus.

- Extension or retroversion (20°): gluteus maximus (if put out of action, active standing from a sitting position is not possible, but standing and walking on a flat surface is); dorsal fibers of gluteus medius and minimus; adductor magnus; and piriformis. Additionally, the following thigh muscles extend the hip: semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and long head of biceps femoris.

- Flexion or anteversion (140°): iliopsoas (with psoas major from vertebral column); tensor fascia latae, pectineus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, and gracilis. Thigh muscles acting as hip flexors: rectus femoris and sartorius.

- Abduction (50° with hip extended, 80° with hip flexed): gluteus medius; tensor fascia latae; gluteus maximus with its attachment at the fascia lata; gluteus minimus; piriformis; and obturator internus.

- Adduction (30° with hip extended, 20° with hip flexed): adductor magnus with adductor minimus; adductor longus, adductor brevis, gluteus maximus with its attachment at the gluteal tuberosity; gracilis (extends to the tibia); pectineus, quadratus femoris; and obturator externus. Of the thigh muscles, semitendinosus is especially involved in hip adduction.

Sexual dimorphism and cultural significance

In humans, unlike other animals, the hip bones are substantially different in the two sexes. The hips of human females widen during puberty.[20] The femurs are also more widely spaced in females, so as to widen the opening in the hip bone and thus facilitate childbirth. Finally, the ilium and its muscle attachment are shaped so as to situate the buttocks away from the birth canal, where contraction of the buttocks could otherwise damage the baby.

The female hips have long been associated with both fertility and general expression of sexuality. Since broad hips facilitate child birth and also serve as an anatomical cue of sexual maturity, they have been seen as an attractive trait for women for thousands of years. Many of the classical poses women take when sculpted, painted or photographed, such as the Odalisque, serve to emphasize the prominence of their hips. Similarly, women's fashion through the ages has often drawn attention to the girth of the wearer's hips. Hip piercing is a fashion where piercing is done close to hip bones near the belly.

See also

- Haunch

- Hip examination

- Hip replacement

- Snapping hip syndrome

- Body shape

- Waist-hip ratio

- Hip dysplasia (human)

- Sexual dimorphism

- Femoral Acetabular Impingement

Notes

- ↑ Latin coxa was used by Celsus in the sense "hip", but by Pliny the Elder in the sense "hip bone" (Diab, p 77)

- ↑ MediLexicon

- ↑ Field (2001), p 80

- ↑ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 381

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Faller (2004), pp 174-175

- ↑ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 365

- ↑ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 378

- ↑ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 379

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 367

- ↑ Platzer (2004), p 196

- ↑ Palastanga (2006), p 353

- ↑ Because the neck is wider in front than at the back.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Platzer (2004), p 198

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Platzer (2004), p 200

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), pp 383, 440

- ↑ Clemente (2006), p 227

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 386

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Platzer (2004), pp 244-246

- ↑ Platzer (2004), p 238

- ↑ "Reproductive Anatomy and Physiology". The Harriet and Robert Heilbrunn Department of Population and Family Health. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/hs/pubhealth/modules/reproductiveHealth/anatomy.html. Retrieved June 2009.

References

- Clemente, Carmine D. (2006). Clemente's Anatomy Dissector. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0781763398. http://books.google.com/books?id=oEMvo2exmJgC&pg=RA2-PA227.

- Diab, Mohammad (1999). Lexicon of Orthopaedic Etymology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9057025973. http://books.google.com/books?id=fstFQVnw8-wC&pg=PA200#PPA77,M1.

- Faller, Adolf; Schuenke, Michael; Schuenke, Gabriele (2004). The Human Body: An Introduction to Structure and Function. Thieme. ISBN 3-13-129271-7.

- Field, Derek (2001). Anatomy: palpation and surface markings (3rd ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 0750646187.

- "Hip Region". MediLexicon. http://www.medilexicon.com/medicaldictionary.php?t=77165.

- Palastanga, Nigel; Field, Derek; Soames, Roger (2006). Anatomy and human movement: structure and function (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 0750688149. http://books.google.com/books?id=rRtPExr9Hz8C&pg=PA353.

- Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

- Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. 2006. ISBN 1-58890-419-9.

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||